|

|

|

| |

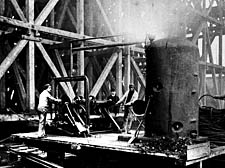

Building Barlow’s shed

The men who designed the original magnificent 19th-century Gothic building are being justly celebrated – but there is little recognition of the labourers whose blood, sweat and tears went into its construction

Local historians – supported by Holborn and St Pancras MP Frank Dobson – are calling for a plaque to commemorate more than 1,000 workers who built St Pancras station and the Midland Grand Hotel over a period of 12 years, starting in 1864.

It has been suggested a particular tribute should be paid to the Irish navvies – whose descendants settled in north London – who performed the brunt of the back-breaking work for little money, enduring appalling conditions.

Those responsible for the highly praised rebuilding work have announced that they do have plans for a visitor centre at the station which will include as much information as available about the Victorian labourers.

According to Camden historian Peter Barber little has been written about the workers who built the station, “but we know that life was cheap and extremely harsh,” he says.

“There was no health and safety on the building sites in those days and many would have been seriously injured during construction and probably died.”

On top of that there was a serious cholera outbreak locally and they had to cover over the River Fleet, which had become a running sewer.

Mr Barber, a member of Camden History Society and Head of Maps at the British Library, believes that a plaque to workers who built the station would be truly fitting.

“Poet John Betjeman, who fought British Rail when they wanted to knock the station down in the 1960s, is rightly being remembered.” he says. “They are erecting a statue to him on a platform.

“We also know all about the great architect who designed the station, George Gilbert Scott, and engineer William Barlow. They have been written about in various books about St Pancras. But there is little mention of the men who did the hard and unrelenting physical work.”

An entire community of 4,000 homes at Agar Town was demolished to make way for the station and hotel.

The town was described as a “festering slum” by the authorities, but it would have been a terrible upheaval for the residents who, apparently, were never compensated but merely removed to live in other dirty dwellings.

Simon Bradley, whose new definitive book St Pancras Station suggests that the residents of Agar Town were sacrificed for the sake of the station: “To compound the cruelty it is likely that many of the men from Agar would have had to return to the demolished site of their former homes to beg for work on the station.”

On top of that, the new railway cut right across the St Pancras Old churchyard. Mr Bradley says: “We know about that because the reinterment of the coffins and bones was supervised by a young Thomas Hardy, in the days before he became a writer.”

Frank Dobson, who reviewed Mr Bradley’s book earlier this year, says: “We don’t know how many workers were injured or killed in the process, whether they were local or came to London specially for the work.

“It may be that all the records have been destroyed or even that no records were kept. But I would like to have known.”

In 1845 there were 200,000 navvies in Britain working on 3,000 miles of new line.

They were a colourful breed of men who worked like pack animals using picks and shovels and gunpowder to blow holes in the ground. They also drank prodigiously and fought regularly, although mainly each other.

In his book The Railway Navvies, author Terry Coleman describes how each navvy could devour two pounds of beef and a gallon of beer a day.

He writes: “They wore distinctive moleskin trousers, double canvas shirts, and velveteen square-tailed coats, hobnail boots, gaudy handkerchiefs, and white felt hats with brims turned up.”

Railway engineers rarely kept any count of the men killed, he says. “It was customary to ignore the navvies, as if railways built themselves.”

Coleman reports how a visitor described a gang of 12 navvies digging down in the shaft at nearby Belsize tunnel: “Half of them with pickaxes, tearing away at the rough clay and accompanying every stroke with a noise that was half grunt, half groan.”

The Irish navvies played a crucial role in shaping Camden and Kentish Town, both physically and socially.

Victorian Kentish Town is surrounded by bricks laid by the huge numbers of immigrants who arrived in London after the great famines of the 19th century. Camden Town, in particular, has long been recognised as a place where people from all over the UK gather.

During the early years there were a lot of pub fights involving the navvies of various nationalities who were building the railway.

Faced with this growing problem, a local solution evolved: The Windsor Castle pub for the English, The Edinburgh Castle for the Scots, The Pembroke Castle for the Welsh and the good old Dublin Castle for the Irish.

PETER GRUNER

> Click here to buy your copy. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|