|

|

|

| |

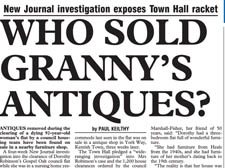

Flashback to February 8th 2007, and our lead story on the front page |

Clearing out old folks’ homes is a lot easier than clearing up the scandal

WHY is the Town Hall so desperate to keep a report secret that officials have used the law three times to stop elected councillors and this newspaper from discussing it?

At a late-night meeting on Tuesday, councillors were about to discuss a heavily censored copy of a report behind closed doors when one of my colleagues protested.

The ‘Part Two’ exemption – used when councillors have to discuss legally or commercially sensitive material – was invalid and the facts should be heard in the open, he argued.

Councillors, including the committee chairman, agreed. But they were stopped in their tracks by a furious reaction from a senior official in the chief executive’s office, backed up by the duty lawyer.

When the official refused to allow the item to be heard, chairman Chris Philp muttered “We shall not be part of a cover up” and adjourned the hearing.

To understand the full story you need to go back a year, when the New Journal revealed how valuable furniture removed from the council flat of dying 92-year-old Dorothy Robinson (pictured right) ended up on sale in nearby antique shops.

Our investigation (inset, left) showed that out of 1,200 ‘clearances’ carried out on council homes each year, not a penny, not an earring, not a single heirloom, had been recovered from the homes of tenants who had died or been moved into care.

Our story prompted a ‘review’, then an ‘investigation’, then a report in August in which the Special Investigations Team – an in-house team – said no crime had been detected.

But the August report referred to a second, internal, report “made available to senior managers” – but never seen by councillors. We applied to see the secret report using the Freedom of Information Act, but were denied.

After three months of argument, the cross-party housing and adult social care scrutiny committee won the right to see a heavily censored version of it.

So what is in the report? My sources tell me it reveals that a blind eye was turned at the Town Hall to a suspected racket, and that the internal investigators conclude that because staff were not acting against written rules and no one reported anything as a crime, they can take no action.

Officials would like all this to go away. But it won’t.

Drawing inspiration from the real life dignity of men’s labour

THANK goodness there’s another chance to see a show of paintings by Joseph Herman, whose works take me back to Émile Zola’s raw novel, Germinal.

Herman, who fled to Britain from Nazi Germany in the late 1930s, eventually settled in Camden after living in a Welsh mining village.

And that’s why I associate Zola with Herman – because his portraits of Welsh miners have that real life quality about them.

Unlike most artists, Herman was drawn to the dignity of labour, and the depths of the human spirit, expressing ideas in stark and sombre colours.

He became one of the most discussed artists in the 1950s and 1960s, and settled in the borough in 1965, where he lived until his death, aged 89, in 2000.

His son David lives in West Hampstead.

The last time I saw Herman’s paintings was four years ago in an exhibition at the Boundary Gallery in St John’s Wood.

They are now handling his estate and have loaned some of them to the Flowers Central gallery in Cork Street, Mayfair, where you can see them from Monday.

After years in the hot seat at No 10, Alastair’s now finally feeling the Heat

ALASTAIR Campbell has got the hump with the media.

He talked of falling journalistic standards and the negative bashing of politicians at a lecture on Monday evening.

But, on a more personal note, he also spoke about how he can’t wean his daughter off the celebrity magazine, Heat.

He described how he attended a magazine awards ceremony and was “grumping away about my failed attempts to stop my teenage daughter from buying Heat and its ilk on the grounds that they are not just trivial and devoid of values, but cruel and demeaning of women, in particular…”.

This threw up memories of a chat I had with Campbell a few years ago at a Gospel Oak School function about the number of young teens I’d seen smoking in Camden Town, despite all the health warnings. I said they were mostly poor kids, and didn’t he think the government should do something about it? By that I meant shouldn’t New Labour crack down on the big tobacco companies. Campbell was then one of the most influential figures at No 10, and he knew what I was getting at. Dismissing my concerns, he said: “Can’t do anything. You can’t let the genie out of the bag.”

In other words: ‘Can’t you see it’s too big a subject? Too many big people will be upset.’

I’m sure he and his partner, Fiona Millar, are worried about the sexualisation of children in the media and the commodification of sex, and maybe something of that is bugging Campbell now.

You need more than new laws and regulations to tackle social ills – poverty, cultural deprivation, growing illiteracy among children: all these require the intervention of fundamental social reforms which, in turn, means the diminution of the powers of the big corporations.

In the process, the genie will be let out of the bottle.

Campbell also talked about the “rampant commercialistion” of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire.

Murdoch also became the theme of a talk by Peter Wilby, ex-editor of the Independent on Sunday and New Statesman, at a conference of journalists at the HQ of the National Union of Journalists, in King’s Cross.

Wilby described Murdoch as a “natural monopolist.” He wasn’t the worst of proprietors, but his ownership of too many papers and TV channels was unhealthy, argued Wilby.

Wilby would probably agree with Cambell’s strictures on the “negativity” of the media but he’d place most of the blame on Murdoch who, since he started to buy up papers in the 1980s, has dumbed down journalism.

Murdoch didn’t lay down editorial lines for his editors but, by a strange coincidence, they were all in favour of the Iraq war and were mostly anti-Europe – all in harmony with Murdoch’s view of the world. But, in answer to a question at the conference, columnist Victoria Brittain went further – Murdoch’s papers, she said, were part of the “daily poison of the tabloids,”

Showing Lionel’s courage when faced with bullets in Bali and injustice in the newsroom

I’VE been in some tough spots as a journalist, but none were near as dangerous as the one my old friend Lionel Morrison found himself in.

This week, with the death of the bloody Indonesia dictator Suharto – he was responsible for the massacre of more than 600,000 – Lionel told me about his own days there when he was working as a journalist.

“Suharto’s coup, led by army generals, suddenly erupted in October, 1964, and from the hotel and Press club you could hear the shooting,” Lionel told me over the phone from South Africa, where he is visiting relatives.

“To go to the hotel from the club you had to bend low because bullets were whistling overhead. A day or so after things blew up, I saw my secretary led away by two men. Later, her body was found, along with dozens of bodies, in a nearby canal.

“I’ve never really talked about this before, I’ve had a kind of blockage because my girlfriend, Habita, was killed in the coup.

“She had gone home to Bali to see her family, and then she disappeared.”

Lionel, who lives in Queen’s Park, was a former president of the National Union of Journalists, and campaigned in the 1970s and 1980s to persuade newspapers and TV stations to employ more black journalists. There are still few of them in mainstream media but 20 years ago or so you wouldn’t see black face in a newsroom at all.

His fascinating book, published recently, A Century of Black Journalism in Britain, tells the story.

I

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|