|

|

|

| |

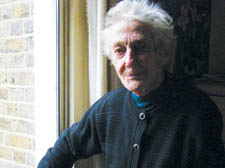

Angela Sinclair: ‘The health centre was designed to cheer patients up’ |

‘Beacon of light’ health centre in need of tender loving care

Widow of wartime doctor based at threatened building urges NHS chiefs to think again

ANGELA Sinclair must be one of the last links with a pioneering group who made Finsbury Health Centre the envy of the nation.

The centre, where her husband worked during World War II, opened in 1938, founded on socialist principles that would later become the bedrock of the National Health Service. For the first time, doctors worked side by side with nurses, social workers, radiographers and physiotherapists.

The health centre, in Pine Street, is arguably Islington’s greatest success stories – but it is now threatened with closure.

Designed by renowned architect Berthold Lubetkin, the centre’s name became synonymous with progressive health care and attracted the finest professionals, including Ms Sinclair’s husband, Dr Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, who died four years.

She said: “As war approached, it was suggested Kenneth apply for a post of civil defence medical officer to the borough of Finsbury, for which his experience during the Spanish Civil War was useful.

“He found himself heading an autonomous municipal department employing several hundred staff in first-aid posts, a mobile medical unit, rescue parties with light engineering capacity, motorised stretcher parties and a mortuary.

“They were based in a well-organised depot at Finsbury Health Centre, within which Tecton [Lubetkin’s architectural practice] had designed the first air-raid shelters.”

Dr Sinclair-Loutit was awarded an MBE for his work at the centre and was so popular he was later invited to run as a candidate to become MP for the borough but declined. His widow said: “I wasn’t really into politics at the time, so I advised him to take another job offer with the World Health Organisation.

“He opted for that, which became the basis of his long future career.”

She added: “He really admired Finsbury Health Centre and everything it stood for.”

Lubetkin had proclaimed on the centre’s opening that “nothing is too good for ordinary people”.

Ms Sinclair said: “Lubetkin was determined that the centre’s design should encourage the public to become healthier, for instance by including its glass brick facade and cheerful murals for their ‘sunny and airy’ effect.

“He was enthusiastic about getting people to adopt healthier lifestyles. There is a great open-air feel to the health centre – it is like being outside, inside.

“That was a notable feature of the design. It has a frontage of glass that was especially designed to reflect light into the building. The health centre was designed to cheer patients up.”

To her, the uncertainty about the future of the centre is part of a wider trend, a feeling that historic Islington is under attack from all sides. From the back window of her home, she can see Highbury, the former Arsenal stadium, being turned into flats. “If new buildings are judged as superior to older ones, why not tear down Islington’s delightful heritage of Georgian houses – many of which much require repairs and refurbishments?” she asked.

Islington Primary Care Trust, which is considering the health centre’s future, says its responsibility is not to maintain historic buildings but to improve the health of patients.

Ms Sinclair said: “I don’t think they will be safeguarding their patients if they do not care about their buildings.”

The trust will unveil its plans for the centre at a board meeting at 9.30am on September 25.

Anyone with an interest in the centre is invited to attend the meeting at the trust headquarters in Goswell Road. |

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|