|

|

|

| |

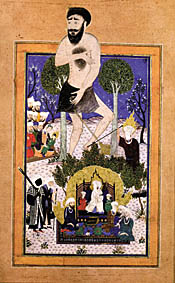

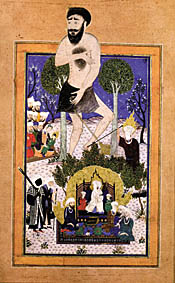

The Giant Uj and the prophets Moses, Jesus and Mohammed,

early 15th century

Brass and silver casket with a four dial combination lock,

from Jazira, first half of 13th century

Carved ivory box from Umayyad, Spain, 960AD

Professor David Nasser |

Islamic art and the Jewish connoisseur

Professor David Nasser Khalili

owns the largest collection of Islamic art in the world, but

it's not about financial investment, he tells Dan Carrier

BUYING art is not an investment – it is about safeguarding

cultural items for future generations, and making them accessible

for people today.

This is the view of the largest private collector of Islamic

art in the world, Professor David Nasser Khalili, who will be

discussing his collection of Islamic art on Wednesday at the

Jewish Book Week.

And although many find it surprising, Prof Khalili is not a

Muslim – he is Jewish.

“I simply happen to be fascinated by Islamic art,”

he says.

And Prof Khalili wants the world to join him in celebrating

the superb legacy of Islamic architecture, calligraphy and art

in general.

He is from Tehran – and that means he feels the Iranian

Islamic world is as much his cultural heritage as his Jewish

background: “I grew up to with Islam and its beauty,”

he says.

Prof Khalili, who teaches at the School of Oriental and African

Studies in Bloomsbury, has used a self-made personal fortune

to amass over 20,000 artefacts.

His fortune stems from property, but he had made money as a

young boy. When he was 14 he spent a summer holiday writing

a book about the world’s 25 greatest geniuses. It became

a best seller, and he used the cash to fund travel from his

native Tehran when he was a young man, and from that, fuel his

interest in his field. Astute property deals secured his fortune

– he hit the news when he sold a mansion in Kensington

to Formula One boss Bernie Ecclestone for an approximate £70

million.

But art is where he wants to spend his fortune, and it is estimated

in 35 years he has accumulated treasures worth at least £500m.

He says his dream is not to be an art collector, someone who

decorates their home with beautiful objects. Instead he wants

to be an art philanthropist, some one who safeguards public

access to the world’s treasures – a philosophy that

was behind his offer to hand over his collection to a permanent

display in his adopted home of London.

“I’m driven as a collector by a passion for art and

a love for the contribution to humanity,” he says.

And Prof Khalili says every piece he buys has a place in his

heart.

“I consider my collection to be a symphony; everyone in

that symphony has a role so you cannot specifically say one

is more important than another.”

The idea of forming a collection based on Islamic influences

gives him a huge scope as a collector, he says. Islamic art

is not confined to a religious or ethnic pigeonhole.

He said: “The term ‘Islamic art’ broadly describes

works produced by Muslim artists for Muslim patrons. ‘Islamic’

does not imply that the art is exclusively religious in content

or use, indeed a significant portion is secular. It is ‘Islamic’

because its artistic vocabulary is partly rooted in Muslim philosophical

thought and shaped to some extent by the spirit and doctrines

of the Muslim faith. This is why it can be discussed as a whole

in spite of the wide geographical area in which it was produced

and the fact that Muslim artists and architects have been influenced

and enriched by the artistic traditions of the other cultures

with which they came into contact.”

And he believes by celebrating the beauty of Islam, he can help

educate people – and change their perceptions. He hopes

this will bring a greater understanding between Muslims and

the West.

He said: “How can ignorance and prejudice about Islam be

dispelled? One way is to show and publicise the amazing achievements,

what they have brought to the world.”

He has, for the first time, collated manuscripts of the Qu’ran

and systematically assembled them in a chronological order to

demonstrate their growth and the development of calligraphy

in religious texts.

He has done the same with other artefacts such as glass and

earthenware, to allow the layman to understand the historical

growth of Islamic art and its effects and influences on the

societies that produced it.

One of his overwhelming aims is to use his collection as a unifying

influence.

He said: “I have always believed that religion and politics

have their own language but the language of art is universal.

“You cannot find a more unifying factor than the universality

of art. As a Jewish collector of Islamic art, I consider my

contribution to Islamic culture as if from one member of the

family to another.”

|

|

|

|