|

|

|

| |

From Pointless Park to Karl Marx Square

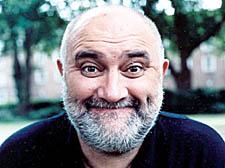

Why are the middle-class such

a worried lot? Peter Gruner finds out from Alexei Sayle

The Weeping Women Hotel by Alexei Sayle

Sceptre, £12.99

THERE’S an evocative scene in Alexei Sayle’s new book

when one of the main characters, Harriet, goes to a gym called

Muscle Bitch where there are “demented women running on

treadmills with crazed expressions”.

Somehow in The Weeping Women Hotel everyone is running, desperate

to keep up with appearances, or with their more successful and

wealthy or wise neighbours and friends.

Sayle says that as well as being a comedy, his novel takes on

some serious issues. He delights in pricking middle-class pretensions,

like the elevation of gardeners to “tree surgeons”.

“These days everyone gets a standing ovation for something,”

he says.

His own background is distinctly left-wing – his parents

were dyed-in-the-wool communists. And in the book, in the best

traditions of the social commentator, he is as keen to take

humorous pot shots at all levels of society. There are sly political

digs. He mentions that “Marxists are taking over the magazine

Puppetry Today” – an oblique reference to the huge

perceived influence of the former magazine Marxism Today, which

appeared at a time of fears about communist infiltration in

the media.

The novel weaves an unpredictable and darkly humorous tale set

in north London, around the rigidly landscaped ‘Pointless

Park’, where over-priced gastropubs, gyms and focaccia-eaters

are colonising former working class areas. Local shops close

down to be reopened as a ‘f***ing Starbucks”.

Bloomsbury resident Sayle is strongly opposed to the loss of

small shops, but he urges action rather than moaning and mourning.

He tells me: “People are right to be concerned, but it

is up to them to support the small businesses. A Bagel Factory

opened in Lambs Conduit Street – and closed down through

lack of support.”

His novel deftly captures the female voice, particularly in

his portrayal of Harriet, mousy and overweight, who keeps a

tally of her friends’ phone calls and is petrified of offending

anybody.

Helen is her beautiful, over-achieving sister, and Toby is Helen’s

peculiar husband, a charity worker for the Penrith Fairground

Disaster Fund, whose main purpose is to “avoid giving any

money to anybody involved in any way in the great Penrith Fairground

Disaster”.

Sayle’s wicked humour takes a sideswipe at middle-class

preoccupations. Enjoyable dinner-party talk with Harriet’s

sister’s circle of friends centres around “furious

anger about speed cameras, parking fines and getting clamped”

(when they are feeling calm), or mini-breaks and holidays, when

something might be threatening their protective bubble. Decidedly

“fat and ugly”, and keen to turn her life around,

Harriet hires a personal trainer – Patrick – who leads

Harriet in deranged (and rather vicious) martial arts classes,

which involve hurling herself from trees and being kicked in

the shins.

Harriet isn’t completely convinced about Patrick’s

cult-like discipline. However, the exercise certainly seems

to have an effect, and Harriet is slowly transformed from “pot-bellied

and lumpy” into a confident stunning beauty.

Sayle mixes the mundane normalities of life with the unexpected,

and downright absurd. His eccentric characters are instantly

recognisable.

Even Harriet’s sensible sister has her own peculiarities,

in the form of her inner voice of confirming righteousness,

Julio Spuciek – Argentinean political prisoner and puppeteer,

whom she consults on every major decision in her life and is

a constant reassurance that she’s doing the right thing.

The novel both challenges and confirms stereotypes, holding

up a mirror to north London society, and showing the cracks.

In short, witty sentences or hilarious situations, Sayle manages

to address many topical issues, including class, immigration

and the changing face of Britain – new town and tarmacked

– which is personified by Pointless Park with its blank

walls and metal fencing.

This is all very far from the world of Harriet’s childhood

‘up north’ when parks were parks, bandstands and all.

Sayle asserts that: “Those into whose charge fell the open

spaces during the 1960s were having none of that malarkey –

they couldn’t quite explain to you how a bandstand could

be oppressive of racial minorities while simultaneously putting

down women, they just knew that it somehow did.”

Harriet’s physical and spiritual journey in the novel is

often strange and surreal. She befriends her Namibian gangster

neighbours, who used to dump rubbish on her porch, and of whom

she was once terrified.

The ringleader of this gang, a Mr Iqubal Fitzherbert De Castro,

turns out to be a rather insightful man, and Harriet enjoys

the company of him and his group, finding that they are not

bound by ‘parking tickets, planning regulations and refraining

from putting your rubbish out until after 8.30 at night’.

Through another male character, Sayle shows a certain sympathy

for women. “It occurs to me you all worry too much, all

you women… you know when I am in the newsagents I look

at the men’s magazines and there’s hundreds of them

about their many hobbies – trains, guns, cars, sailing,

Asian women with enormous breasts. But then I look at the women’s

magazines and I see every one of them is to do with self-improvement,

a constant striving to make yourselves one hundred per cent

perfect. Lose weight, get fitter, speak Chinese, knit this,

weave that.”

Sayle’s writing style is sharply witty and his characters

imaginative and offbeat, making this a rich, funny and endlessly

inventive novel.

Speaking about his desolate creation, Pointless Park, Sayle

says even this is not without its beauty.

In the novel, he brings the park alive with a multi-cultural

food fete organised by Columbian immigrants and the Communist

Party. Perhaps this feeling is born of his admitted affection

for some of north London’s more apparently unappealing

edifices, such as Wood Green Shopping City, of which he says:

“It does have a certain monumental style to it. You can

find a sort of beauty in the most unlikely places.”

Talking about life imitating art, Sayle expresses an interest

in the quirky proposal to celebrate Marx’s local connections

– he was buried in Highgate cemetery and lived in Kentish

Town – by renaming Archway Mall, Karl Marx Square.

The proposal for a themed walk to the cemetery and a museum

received such displeasure from the Tories in the House of Commons

that they put down an Early Day Motion suggesting it would be

an insult to the millions who died under communism.

Sayle says: “Marx was a remarkable philosopher – a

man of ideas – but obviously things didn’t go quite

according to plan. He did a lot of his most creative work in

London. But we should distinguish Marx from those who came after

him and claimed to represent his ideas.” |

|

|

|