Louise Jameson plays Mrs Green

Family past: (l-r) Catherine Bailey (Shirl), Linal Haft (Lionel), and Iddo Goldberg (Mike) in the new play |

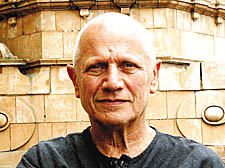

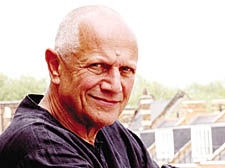

Berkoff’s shivering history

Steven Berkoff may have missed out on his Barmitzvah, but his new play shows he’s a Jew through and through, writes Gerald Isaaman

STEVEN Berkoff, the iconoclastic actor, playwright and director, never went to his father’s Shiva, the traditional seven-day period of mourning by orthodox Jews, because, when his father, Abraham, an East End tailor from Leman Street known as Al, died, he was abroad.

He never celebrated his barmitzvah, the coming of age ceremony when Jewish boys reach 13, because, he says, nobody could be bothered. And he felt ashamed at the time that he had not endured the rite of passage to manhood in the setting of a synagogue, missing out on the customary gifts of gold fountain pens and super watches.

Nevertheless, he rejoices in his East End background, his Jewish refugee family links with Russia and Romania and declaims with exultant vigour: “I am a Jew from my fingertips to my toes, from the top of my hair I’m a Jew. I am Jewish absolutely, and I practice day and night in the Jewish way of life.”

A shy daydreamer as a boy, he is now an impressive 68, ruminating over those early years. And he explains with a touch of guilt: “I’ve been a kind of surrogate goy, learning to speak correctly, wanting to perform Shakespeare, becoming English. Well, I was born in England and I’m an Englishman, but the Jewish thing is in the blood and I have become very drawn back to the past.”

The first play he wrote, East, was about his childhood memories. And the latest one, Sit and Shiver, returns to the theme, but this time deliberately using his own family to conjure up, in a partly fictionalised form, the vivid past that haunts him.

And since it is a comedy, albeit one packed with Talmudic wisdom and insight, which opened with previews at the New End Theatre, Hampstead, last night (Wednesday), the joke is in the title, Sit and Shiver.

Shiva actually means seven days in Hebrew, when the tragic loss of a relative is mourned by the family sitting on low chairs with the legs virtually cut off, relatives and friends coming to ease the pain by creating a cocoon of condolence that enables the bereaved to live on.

“As a child I thought Sitting Shiva was Sit and Shiver,” Berkoff, a big man incongruously dressed in teenager’s jeans and cap, reveals with a grin. “I didn’t want to write a play called Sitting Shiva. I thought Sit and Shiver was a good title because that’s what all the characters do.

It seems appropriate and very poetic. Each one is shivering in their own kind of bubble of hope, desire and need, except for Uncle Sam, who is a kind of King Lear who pulls them all together.”

It is Berkoff’s own father they have come to mourn, unlike the playwright himself who is directing the New End premiere of his tribute to the past. “My real Uncle Sam was an extraordinary man,” he recalls.

“He lived in the East End all his life and was one of the guys who stood up against the fascist Oswald Mosley. He was there in the riots and was even honoured by being in a mural in Cable Street. His face is there.

“He was an amazing character, a wonderful political agitator, orator, speaker, working-class intellectual, a total radical who could quote Dickens, Huxley, Marx, Shakespeare. He would quote reams of Shakespeare at me. And yet he was a trousers cutter all his life.”

Sam’s wife, Betty, partly based on Berkoff’s mother, is there too, and Berkoff himself, as the young actor Michael, who arrives with a Shiksa (unclean Christian) girlfriend, a polite and charming girl whose eyes are rapidly opened to a very different world, hard to comprehend.

And there is another person, a stranger from long ago who arrives to create the denoument, not to be given away here, about an episode in the life of the deceased that shocks everyone and forces them to re-evaluate their views.

“It’s a comedy of Jewish manners, the obsession that Jews have to preserve what they feel about a vital kind of ethics, the family, the home, the food, the friends, the relatives, always honouring things,” declares exuberant Berkoff, who maintains his East End life by living in Limehouse.

“It is all these things, an intensity that is tribal, if not verging towards the neurotic, that perhaps started with the fact that the Jews were an isolated people, wanting to hang on to so much.

“Like anything else, it can become overwhelming, then fanatic, but not fanatic in a religious sense. These people are not violent but they do become extraordinarily protective. The tribal rituals have to be right, as if they preserve Jews as a race. And it keeps us, in a way, from dissipating ourselves.”

He believes, too, that his lack of an orthodox childhood has not denied him his Jewish heritage. “I see myself as a person who has gone through his own particular barmitzvah, which is to find and to define and to somehow shape my beliefs into my work,” is his personal message. “That is the most marvellous barmitzvah, a rite of passage that enables me somehow to condense and funnel life through my particular mind that has been shaped from my family values growing up in the East End.”

Berkoff, known to movie fans for villainous roles in Clockwork Orange, The Krays, Rambo and the Bond movie Octopussy, is a much more serious performer and creator who has presented his own plays and Shakespeare around the word, including in Hebrew, in Israel, among them his adaptations of Kafka’s works.

He worries about the state of television, believing that increasing juvenile crimes of violence are partly down to the brainwashing of successive generations. “We have been corrupting them for years without realising it,” he protests.

“I tend to see television having a very destructive influence on the young.

“We need a revolution to stop it.”

Or perhaps a evening engulfed in the comforting Jewish joy and inspired sentiment of Sit and Shiver.

CLICK BELOW TO SEARCH FOR ACCOMODATION

|