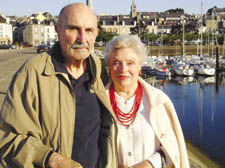

Squadron Leader Gordon Carter and his French wife Janine in Quimper. Left, the couple after their reunion and wedding in 1945 |

The ‘celebrities’ who went back for more

Tony Rennell and John Nichol have tracked down the heroes of the Second World War who redefined bravery, writes Gerald Isaaman

Home Run: Escape from Nazi Europe.

By Tony Rennell and John Nichol. Viking, £20.

order this book

WHAT is it that makes people so brilliantly brave and oblivious of danger when their country is engulfed by war and invading Nazi soldiers patrol their once-free streets? Tony Rennell shrugs his shoulders and insists he has no coherent answer.

Yet given his work as a popular historian telling the amazingly courageous and poignant stories of those who confronted the hated enemy, regularly putting their lives on the line, you might think he had a clue.

And more so too as he himself had his family sitting round his bed in the Royal Free Hospital, Hampstead, expecting him to die after a bug played hell with his vital organs and he was warned of the worst.

Yet, again, he survived the coma to complete the final third of Home Run, the dramatic stories of shot down airmen during the Second World War who somehow managed to escape capture and find a precarious route home across the Channel – so that they could fly back into battle again to defeat Hitler.

They display some kind of indomitable innate spirit exposed in all their stories. So too the young French, Belgian and Dutch compatriots who helped them seek safety, despite notices plastered in their streets that anyone caught doing so would be shot – many were, or ended up in concentration camps.

“It’s quite amazing, incredible really,” says Rennell, a 59-year-old former Fleet Street journalist, as, still in pain and awaiting further operations, he gazes over the rooftops of Hampstead from his penthouse flat in Lyndhurst Gardens.

“Suddenly these young people, just 19 or 20, were flying home, looking forward to their eggs and bacon in the mess, when they were shot down and, within half a minute, were on the ground, on their own, frightened and without a clue how to cope.

“They were not like the young people of today, who are sophisticated and have travelled abroad and speak foreign languages. This was a different generation who hadn’t gone beyond their home town, let alone to another country. Their courage was stunning.”

And he feels it more so because much of their courage has since been ridiculed, he believes, in television programmes like ‘Allo ‘Allo and Dad’s Army – horror turned into humour.

“That whole war generation has become a bit of a joke which nobody has wanted to take seriously,” he protests.

“It wouldn’t happen now. In our spoilt society, we’d all be questioning why someone has to climb into a bomber night after night, does 50 missions knowing that his chances of survival are about 50-50, if that. They’d be calling health and safety and saying ‘I’m not getting into that airplane’.

“But in the 1940s people were just terribly, terribly brave – stupid some might say. But they did it. And I admire that so much.”

Indeed, Home Run is the third book about the Second World War on which he has collaborated with John Nichol, the RAF flight lieutenant whose Tornado was shot down over Iraq during the first Gulf War in 1991, before he was captured and paraded to the world on television.

It was born out a chance glib comment Rennell made in their last book, Tailend Charlies, that rarely did any of the bomber crews shot down make it home.

An expert reading the manuscript told him that up to 4,000 men triumphed over the tragedy of crashing in a foreign field, though some were treacherously given away to the Nazis.

“There were traitors galore,” says Rennell. “People like Harold Cole in divided France. But while I had always taken the common view that, in 1940, the French acted appallingly, retreating and surrendering, making scandalous deals with the Germans, there were those who fought the enemy in any way they could.”

While Nichol’s task has always been to meet the victims and, through the experience of his own suffering, tap the emotions of their war, Rennell too travelled to Brittany to meet Squadron Leader Gordon Carter and his French wife Janine in their retirement flat in Quimper.

Carter managed to get himself shot down twice over France, the first time escaping across the Channel in the dirty hold of an old trawler.

But that was not before he had fallen in love with the sister of one of the French Resistance fighters.

“They were in love in a very courteous sort of 1940s way – there was nothing untoward, holding hands was the best they could do and maybe there was a chaste kiss now and then,” he records.

“And he promised her, ‘I’ll come back for you,’ though nobody at that time had any expectation of what would happen next day, let alone in six months or a year.”

But although shot down a second time and ending up in a PoW camp after a horrendous forced march across Germany, Carter returned to his love and married her.

“And there they were, this lovely old couple with his RAF uniform laid out, together with a little piece of silk from his parachute,” says Rennell.

“It sounds a bit patronising to say they did it for love. Love is not the right word to describe it.

“It is one of the great stories of heroism and humanity that we tell in this book, and which I love telling because today’s society is bereft of heroes. We have celebrities instead. And they are not real people.”

|