Edmund Romilly |

Churchill’s descendant shows novel approach

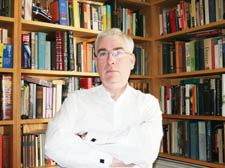

The great-nephew of the war-time leader may be a barrister, but he always wanted to be a writer. Sunita Rappai finds out why

SKINNER by Edmund Romilly,

Apex Publishing Ltd, £5.99 order this book

EDMUND Romilly, great-nephew of former prime minister Winston Churchill and great-great-great grandson of abolitionist and law reformer Sir Samuel Romilly, claims to be working class.

The criminal barrister from Kentish Town, 55, who has just had his first novel published, says: “I’m working class because I have to work. That’s how I see myself.

“My father died without leaving a will. If he had left a will almost certainly I wouldn’t have to work for a living but he didn’t and so I do. My mother says I am “uprooted county” because there was land in Herefordshire and all sorts but all that’s gone now.”

It’s impossible to avoid the subject of class when talking to Romilly, partly because of his illustrious pedigree, and partly because he has chosen to set his first novel, Skinner, in a grim, working class bedsit in Belsize Park – surely a million miles away from his own privileged background?

Not so, according to Romilly. “I lived in a lot of bedsitters when I was a student,” he says, from the home in Little Green Street he shares with his partner, Deborah.

“My background isn’t all illustrious – certainly there are lots of black sheep.

“I’m just rather sceptical about the notion of class. I know it’s said even now there is a class system but I don’t believe it really.

“There’s a council estate just up the road and there’s this street which I suppose is mostly middle class and we get on very well. Our kids go to the same school. I don’t think it’s as much a factor as it’s thought.”

In fairness, Romilly’s own background is less stereotypically upper crust than one might think. Educated at a French school in Pimlico until the age of nine, he was “kidnapped” by his father Giles and spent a year in America with him and his older sister, Lizzy.

“My father was a prisoner of war during the war,” he says, “and when he came back he was filled up with barbiturate drugs which were new in those days and thought to be wonderful. In fact he became addicted to them.

“My mother left one morning and was going to divorce him. So he kidnapped us both and took us to America. The courts sequestrated all his property so we didn’t have any money and we lived like tramps for about a year.”

When they came back, the children were sent to boarding school – Romilly to Marlborough in Wiltshire – and then divided their time between their parents until Giles Romilly died of a drugs overdose in 1967, when Edmund was 16.

Without an inheritance, Romilly, who says he always wanted to be a writer, decided to follow the family tradition and eventually qualified as a barrister in 1983. He has been working in Chambers in Temple ever since – and writing whenever he can.

Romilly’s unconventional background – sort of disenfranchised upper-class radical – and the fact that Skinner was actually written some 20 years ago – probably goes some way to explaining the curiously anachronistic, dated feel of his writing.

The book, written in the first person, seems like a throwback to the kitchen sink drama of the 1950s. It tells the story of John Skinner, a builder whose life is going steadily down the pan. His marriage has broken down, he’s living in a grotty bedsit and he starts hearing strange voices in his head – which eventually lead him to kill.

Quite apart from the relentlessly downbeat subject matter, the book also feels rather insubstantial. At around 35,000 words, it’s roughly half the size of an average novel – and Skinner himself has perhaps too little depth to make you really care what happens to him.

“It was written as an academic exercise,” he explains when I put all this to him. “I wanted to see whether I could write a book about someone who becomes schizophrenic, in the first person, portraying someone who was not like myself at all.

“There was a review in one newspaper where the guy said he started off by being an anti-hero and ends up being no hero at all. But there was no deliberate attempt to make him unsympathetic or sympathetic. It wasn’t a commercial enterprise at all.”

Tellingly, he says his biggest influence as a writer is Georges Simenon, the Belgian creator of the Inspector Maigret books who also tended to focus on ordinary people living extraordinary lives.

“There was a book he wrote called The Glass Cage and it’s about a nonentity who has a boring job, living with his wife in a boring flat in Paris and then he suspects his wife is having an affair and he turns around and kills her.

“A lot of his books are like that, about passion and jealousy and the things that people who can seem nondescript do. The trouble is, although he was deeply fashionable at one point, he just isn’t anymore.

“I don’t actually see people as being that different to each other,” he adds. “It must be pretty boring if you just write about what you know. To an extent, it’s a challenge, isn’t it?

“How much you can empathise with other people – how much you can understand them from the outside.”

|