|

|

|

| |

Walk with the ghosts through Gospel Oak

From farmland to polluted industry, the former village has a rich history, writes Dan Carrier

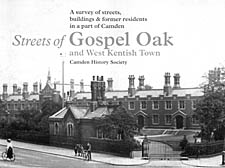

THE STREETS OF GOSPEL OAK

Camden History Society, £7.50.

THE Stables Market is where drays which pulled freight along the canal would find shelter. Now it is a centre for London’s fashion industry. But before the canals and railways changed the face of Chalk Farm the area had still been associated with the horses’ role in industry.

When Chalk Farm was fields, it was used for growing horse feed to supply the capital. The word Haverstock itself comes from Old English, and means ‘Place of Oats’.

Such nuggets of the past are on every page of this new publication from the Camden History Society.

The society has split the borough up into its original villages and then despatched members to uncover the secrets of the area. They have already covered Hampstead, Belsize, West Hampstead, Primrose Hill, Bloomsbury, Holborn, St Pancras and both Camden Town and Kentish Town.

Focusing on how Camden developed, these guide books – which suggest walks and what you should be looking out for – describe everything from how a place got its name through to who built what, when and why.

For example, the history includes a passage about the Vandecasteele brewery of Chalk Farm. It was run by Louis Vandecasteele, a Belgian who brewed German and Czech-style lagers in 1860 – the earliest to do so in the UK.

Just yards from where it once stood is Belgo, the Belgium beer and seafood restaurant – a strange coincidence.

Next to Belgo, Chase Cottage, on what is now the petrol station on Chalk Farm Road, was home of Russian-born photographer James Monte in 1871. His three sons became pioneers of early British cinema, travelling round the country showing film clips.

We learn how Gospel Oak’s rural past was bricked over as London expanded. The people living there 300 years ago made their living supplying milk to Londoners, and this lasted up to the latter part of the 18th century, when it gave way to producing fodder for working horses.

But by the late-Georgian period, agriculture was losing out to house building. Lord Southampton – whose name still graces roads and pubs – sold land in 1840 to speculative builders.

The coming of the railways added to this home-building spree. Two up, two downs for railway workers were built, and industry was also spurred on by the new lines.

Kentish Town and Gospel Oak became known for piano making.

With this surge in light industry came the accompanying retail trade – the workers needed places not just to live but to buy food.

By 1870, the Queen’s Crescent market was thriving. Before refrigeration it was known for meat being sold at knock down prices before it went bad: older locals recall the elderly woman who sold live eels, decapitating them on the spot in front of customers.

But the Victorian homes were, by the turn of the last century, already urban slums.

Few homes in Gospel Oak were well built – fuelled by the need for cheap accommodation, a ghetto developed. Its lowly social status was sealed when the railways encircled the area, puffing tons of noxious smoke into the skies.

Few of the homes had bathrooms, hence the need by St Pancras Council at the turn of the 1900s to build the Prince of Wales baths.

In 1939 a church land survey suggested leaseholders were willing to do outstanding repairs but their plans were frustrated by the outbreak of war.

St Pancras borough council had built homes during the inter-war period – their 1,000th was opened on the eve on the war in 1939. It did not survive: in 1941, 16 people were killed when a bomb hit it.

St Pancras council, and then Camden, changed the outlook of the area for ever in the 1950s and 1960s as whole streets were swept away to make room for new estates.

Streets begun to be demolished in 1963 but gradually housing associations came into vogue and demolition was stopped.

The case of Oak Village is used as an example of the fights that were taking place at the time.

Compulsory purchase orders (CPOs) were due to be issued, but 20 home owners who had restored the Victorian cottages with home improvement grants ran a campaign to persuade the council that it was ludicrous to pull them down. The CPO was heard by the council on 21 December 1966 – and an amendment to stop the demolition of Oak Village was carried.

The preservation of Oak Village is a sign of what we have lost. It is also a lesson for future generations. The stores along Malden Road would be envied by the current occupants. The shopping parade called Newberry Place had shops which included an Italian food warehouse, a grocers, a coffee room, an eel pie shop and a chip shop. No. 10 was the Edwardian childhood home of Alfred Grolsch, who wrote the autobiographical St Pancras Pavements. He grew up over a corn and seed shop. Throw in a blacksmiths and a horse dealership, and this book details the ever changing face of a corner of Camden. |

|

| |

|

|

|