|

|

|

| |

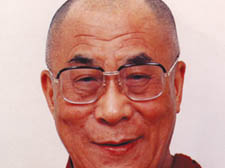

Adventures with the Dalai Lama

When you travel 15,000 miles to meet a holy man in flip-flops, do you leave a carbon footprint? Former GLC chairman Illtyd Harrington recounts his trip to New Delhi for the unveiling of a Peace Pagoda

I LEFT innumerable carbon footprints across the world last week, but I plead not guilty. They were caused by my 15,000-mile journey to New Delhi and back over six days.

My purpose was to attend the inauguration of a spectacular Peace Pagoda in a park situated in the centre of Delhi. The work and organisation was done by the same order of Buddhists who built the London Peace Pagoda in Battersea Park.

Bear with me for a while, for there is a Camden connection.

In the mid-1970s a distinguished Japanese Buddhist scholar called Fujii Guruji (it was Mahatma Gandhi, a friend of his, who added the Guruji bit) moved into a squat in Highgate, not far from the home of Lord David Ennals, then a minister of state in the Harold Wilson government and a friend of the exiled spiritual leaders of Tibet, the Dalai Lama.

Fujii was consistently a champion for peace in a hostile environment, fostered by the aggressive military ethos and physical intimidation of pre-war Japan. This slightly built man was undeterred. He built Peace Pagodas around the world, symbols against the philosophy of nuclear weapons. The one in New Delhi is the latest. I took messages from Mayor Ken Livingstone and Michael Foot, who is president of the India League.

My contribution, in front of several thousand guests and the regional and government Congress party leaders, was listened to by the latter with occasional interest. All of them paid tribute to Fujii, as politicians do all over the world. They court the religious vote. Even Putin goes to Russian Orthodox services.

My scepticism lifted when the Dalai Lama arrived. Beaming and affable, he was reminded by an aide that Lord David Ennals had introduced us more than 20 years ago at the Commonwealth Institute. He wore flip-flops, almost ready for the beach. We chatted and reminisced. He was particularly generous about Ennals’s help.

The Congress leaders droned on, reading their endless scripts. They listened but did not react when I brought up the nuclear agenda of Gordon Brown and David Miliband.

Brown, I said, had apparently muted his criticism of the Iraqi adventure. His party has endorsed the £6 billion so far spent in Iraq and Afghanistan as they agreed to spend £25 billion on improving the Trident submarine’s nuclear delivery.

Cautious diplomat and survivor that he is, the Dalai Lama smiled engagingly as he said: “I’m only a simple Buddhist monk.”

His speech was fresh and spontaneous. He thanked his hosts for the white shawls – a traditional gift – and he summoned a metaphor out of the fly which had just drowned in his glass of orange juice. The fly, he said mischievously, was like all the rest of us, seeking solace.

He praised the spirit and example of Fujii and then suddenly said: “That’s all.” I almost expected him to add “Folks!” like Bugs Bunny.

Returning to his seat, I congratulated him. Then, with a great digital efficiency, he flicked the dead fly from the glass. A rapid funeral service for the fly.

I told him how pleased I was that his friend the actor Richard Gere had been honoured that day for his support of Tibet.

He became even more interested when I told him of a meeting with Gere and the theatre director Frank Dunlop at a wild party in a Kilburn garden 15 years ago. But the Dalai Lama is an animated man in a hurry. His principal aide broke into the conversation apologetically, gently reminding his Holiness that the next stop was the airport and Japan that night. A backward quizzical look from his Holiness, followed by a broad smile, was an indication that my Gere memoir had registered.

So, weary but stimulated, I got back – morally convinced that my carbon footprints had been justified. A polluted haze hangs over Delhi, but a certain political reality shone through – a phenomenon noticeably missing in London.

|

|

|

|

|

|